Does Diving Damage The Brain?

Scuba diving is an exciting and thrilling activity that allows individuals to explore the wonders of the underwater world. However, beneath its allure, scuba diving may pose certain risks to the brain, especially when improper techniques, rapid ascension, or inadequate decompression protocols are involved. While acute decompression sickness (DCS) is commonly discussed as a significant threat, brain damage from scuba diving can occur even in the absence of acute symptoms. This article explores the potential brain damage caused by scuba diving, both with and without the presence of acute decompression sickness, and provides precautions to minimize these risks.

BRAIN DAMAGE IN THE PRESENCE OF ACUTE DECOMPRESSION SICKNESS

Acute decompression sickness, often referred to as “the bends,” is a condition that occurs when nitrogen, which is absorbed into the body during a dive, forms bubbles in the bloodstream upon rapid ascent. These bubbles can obstruct blood vessels and lead to a range of neurological symptoms, including brain damage. When a diver ascends too quickly, the rapid reduction in pressure causes nitrogen to come out of solution and form bubbles that can accumulate in the brain, spinal cord and other tissues.

The brain is particularly vulnerable to these gas bubbles because they can disrupt the normal flow of blood, depriving neural tissue of oxygen and leading to ischemic injury. The severity of brain damage from DCS depends on several factors, including the depth of the dive, the duration of the dive and the speed of ascent. Prolonged exposure to high-pressure environments can increase the likelihood of forming gas bubbles that are large enough to cause tissue damage.

Symptoms of DCS affecting the brain include dizziness, confusion, loss of coordination, visual disturbances, seizures and, in extreme cases, loss of consciousness. If left untreated, these symptoms can lead to permanent brain damage or even death. The damage occurs because the bubbles obstruct the small blood vessels in the brain, preventing proper blood flow and oxygen delivery to the neural tissue. This lack of oxygen (hypoxia) can cause neurons to die, leading to cognitive impairments, motor deficits and other long-term neurological issues.

BRAIN DAMAGE IN THE ABSENCE OF ACUTE DECOMPRESSION SICKNESS

Even when acute decompression sickness is not present, there are still risks of brain damage associated with scuba diving. One potential mechanism for this type of brain injury is chronic exposure to high-pressure environments, which can lead to oxygen toxicity, a condition that results from breathing high concentrations of oxygen at elevated pressures. This condition can damage brain cells by producing reactive oxygen species (ROS), which are highly reactive molecules that can cause cellular damage, inflammation and cell death.

Another potential risk factor for brain damage in the absence

of DCS is repetitive exposure to diving environments without adequate recovery periods. This can lead to a condition known as “chronic dive syndrome,” which may involve subtle but cumulative neurological changes. Some studies suggest that frequent diving without sufficient time for the body to off-gas nitrogen can result in low-level nitrogen buildup in the brain, which could potentially impair cognitive function over time.

Additionally, the physiological stress associated with diving, such as the increased workload on the heart and the body’s need to adapt to fluctuations in pressure, may exacerbate pre-existing brain conditions or contribute to vascular changes that compromise brain health. These factors, when combined with dehydration, fatigue, or hypothermia from cold water exposure, can lead

to minor brain injuries that accumulate over time, potentially resulting in long-term cognitive dysfunction.

POTENTIAL BRAIN DAMAGE FROM NITROGEN NARCOSIS

Another critical consideration in relation to brain health while scuba diving is nitrogen narcosis. This condition, commonly referred to as the “rapture of the deep,” occurs when nitrogen becomes more soluble at high pressures, affecting the central nervous system and leading to symptoms similar to alcohol intoxication. At depths greater than 30 meters (100 feet), divers may experience impaired judgment, motor coordination and cognitive function. In severe cases, nitrogen narcosis can cause confusion, hallucinations and loss of consciousness, increasing the risk of accidents and brain injury.

While the effects of nitrogen narcosis are typically reversible upon ascent, repeated exposure to the condition may contribute to long-term neurological changes. Some researchers suggest that chronic nitrogen narcosis could lead to subtle cognitive deficits or an increased risk of developing neurodegenerative disorders in the long term, though further research is needed to fully understand these risks.

PRECAUTIONS TO PREVENT BRAIN DAMAGE FROM SCUBA DIVING

While the potential for brain damage during scuba diving is a serious concern, there are several precautions divers can take to minimize the risks and ensure safe diving practices. These include proper training, adhering to safe diving limits, and taking steps to manage nitrogen exposure.

Proper Training and Certification: Ensuring that all divers are properly trained and certified through reputable organizations, such as PADI (Professional Association of Diving Instructors) or NAUI (National Association of Underwater Instructors), is essential. Certified divers are taught safe diving practices, including the importance of controlling ascent rates and adhering to depth limits.

Slow and Controlled Ascent: One of the most crucial precautions to avoid decompression sickness and potential brain injury is to ascend slowly. Divers should always follow the recommended ascent rates (no faster than 9 meters per minute or 30 feet per minute) and make safety stops at 3 to 5 meters (10 to 15 feet) to allow nitrogen to safely leave the body.

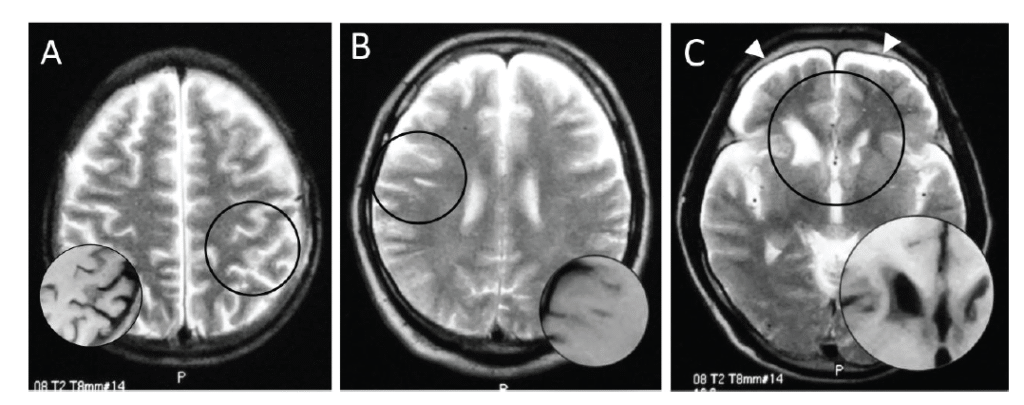

Magnetic resonance images of brains of three Ama divers: hyperintense area on T2-weighted image (circle), corresponding to hypointensity on T1-weighted image (inset). A patchy shadow in the left parietal cortex (A, No. 2), a linear subcortical lesion in the right frontal lobe (B, No. 5), and deformity of bilateral caudate heads and subdural fluid collection (allow heads) (C, No. 11).

Decompression Stops and Tables: Using dive tables or dive computers is critical to ensure that divers do not exceed safe no-decompression limits. These tools help track the nitrogen load accumulated during the dive, providing guidance on when and where to make decompression stops to prevent DCS.

Adequate Rest Between Dives: Giving the body enough time to off-gas nitrogen before the next dive is vital. Avoiding multiple dives on a single day or diving on consecutive days without adequate surface intervals can reduce the risk of nitrogen buildup and the potential for neurological damage.

Oxygen Exposure Management: Limiting exposure to oxygen-rich environments, especially during deep dives, is essential to prevent oxygen toxicity. Divers should avoid prolonged stays at depths greater than 40 meters (130 feet) and be cautious when diving with enriched air (“nitrox”), ensuring that oxygen partial pressures do not exceed safe levels.

Hydration and Avoiding Fatigue: Staying well-hydrated and ensuring adequate rest before and after dives is important for maintaining cognitive function and reducing stress on the body. Dehydration and fatigue can increase susceptibility to diving-related injuries, including those affecting the brain.

Post-Dive Monitoring: After a dive, monitoring for symptoms of DCS, such as dizziness, confusion or difficulty breathing, is essential. If any symptoms occur, immediate medical attention should be sought to prevent potential brain damage or other serious complications.

IN CONCLUSION

Scuba diving can offer a rich and rewarding experience, but it is not without its risks. The potential for brain damage exists both with and without the presence of acute decompression sickness, making it essential for divers to take proper precautions to minimize harm. By following established safety protocols, receiving proper training, managing exposure to nitrogen and oxygen and ensuring adequate rest, divers can significantly reduce the risks associated with diving and protect their brain health. With the right approach, scuba diving can remain a safe and enjoyable activity for both recreational and professional divers alike.

Contribute to the TBI Times