Phineas P. Gage (1823–1860) was an American railroad construction foreman remembered for his improbable: 19 survival of an accident in which a large iron rod was driven completely through his head, destroying much of his brain’s left frontal lobe, and for that injury’s reported effects on his personality and behavior over the remaining 12 years of his life—effects sufficiently ofound that friends saw him (for a time at least) as “no longer Gage”. Long known as the “American Crowbar Case”—once termed “the case which more than all others is calculated to excite our wonder, impair the value of prognosis, and even to subvert our physiological doctrines” —Phineas Gage influenced 19t -century discussion about the mind and brain, particularly debate on cerebral localization, and was perhaps

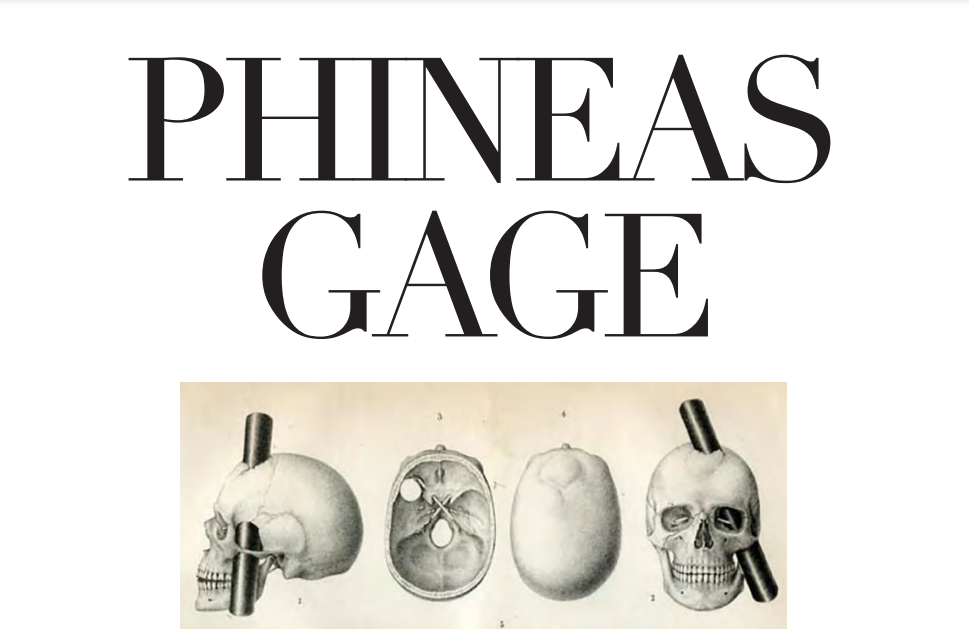

the first case to suggest the brain’s ole in determining personality, and that damage to specific parts of the brain might induce specific mental changes I n 1848, Gage, 25, was the foreman of a crew cutting a railroad bed in Cavendish, Vermont. On September 13, as he was using a tamping iron to pack explosive powder into a hole, the powder detonated. The tamping iron—43 inches long, 1.25 inches in diameter and weighing 13.25 pounds— shot skyward, penetrated Gage’s left cheek, ripped into his brain and exited through his skull, landing several dozen feet away. Though blinded in his left eye, he might not even have lost consciousness, and he remained savvy enough to tell a doctor that day, “Here is business enough for you.”

Gage’s initial survival would have ensured him a measure of celebrity, but his name was etched into history by observations made by John Martyn Harlow, the doctor who treated him for a few months afterward. Gage’s friends found him“no longer Gage,” Harlow wrote. The balance between his “intellectual faculties and animal propensities” seemed gone. He could not stick to plans, uttered “the grossest profanity” and showed “little deference for his fellows.” The railroad-construction company that employed him, which had thought him a model foreman, refused to take him back. So Gage went to work at a stable in New Hampshire, drove coaches in Chile and eventually joined relatives in San Francisco, where he died in May 1860, at age 36, after a series of seizures. In time, Gage became the most famous patient in the annals of neuroscience, because his case was the first to suggest a link between brain trauma and personality change. In his book An Odd Kind of Fame: Stories of Phineas Gage, the University of Melbourne’s Malcolm Macmillan writes that two-thirds of introductory psychology textbooks mention Gage. Even today, his skull, the tamping iron and a mask of his face made while he was alive are the most sought-out items at the Warren Anatomical Museum on the Harvard Medical School campus. Michael Spurlock, a database administrator in Missoula, Montana, happened upon the Wilgus daguerreotype on Flickr in December 2008. As soon as he saw the object the one-eyed man held, Spurlock knew it was not a harpoon. Too

short. No wooden shaft. It looked more like a tamping iron, he thought. Instantly, a name popped into his head: Phineas Gage. Spurlock knew the Gage story well enough to know that any photograph of him would be the first to come to light. He knew enough, too, to be intrigued by Gage’s appearance, if it was Gage. Over the years, accounts of his changed character had gone far beyond Harlow’s observations, Macmillan says, turning him into an ill-tempered, shiftless drunk. But the man in the Flickr photogragh seemed well-dressed and confident It was Spurlock who told the Wilguses that the man in their daguerreotype might be Gage. After Beverly finished her online research, she and Jack concluded that the man probably was. She e-mailed a scan of the photograph to the Warren museum. Eventually it reached Jack Eckert, the public-services librarian at Harvard’s Center for the History of Medicine. “Such a ‘wow’ moment,” Eckert recalls. It had to be Gage, he determined. How many mid-19th-century men with a mangled eye and scarred forehead had their portrait taken holding a metal tool? A tool with an inscription on it? The Wilguses had never noticed the inscription; after all, the daguerreotype measures only 2.75 inches by 3.25 inches. But a few days after receiving Spurlock’s tip, Jack, a retired photography professor, was focusing a camera to take a picture of his photograph. “There’s writing on that rod!” Jack said. He couldn’t read it all, but part of it seemed to say, “through the head of Mr. Phi…”

In March 2009, Jack and Beverly went to Harvard to compare their picture with Gage’s mask and the tamping iron, which had been inscribed in Gage’s lifetime: “This is the bar that was shot through the head of Mr. Phinehas P. Gage,” it reads, misspelling the name. Harvard has not officially decl ed that the daguerreotype is of Gage, but Macmillan, whom the Wilguses contacted next, is quite certain. He has also learned of another photograph, he says, kept by a descendant of Gage’s. As for Spurlock, when he got word that his hunch was apparently correct, “I threw open the hallway door and told my wife, ‘I played a part in a historical discovery!’ ” Popular reports of Gage often depict him as a hardworking, pleasant man prior to the accident. Post-accident, these reports describe him as a changed man, suggesting that the injury had transformed him into a surly, aggressive heavy drinker who was unable to hold down a job. Harlow presented the first account of the changes in Gage’s behavior following the accident. Where Gage had been described as energetic, motivated, and shrewd prior to the accident, many of his acquaintances explained that after the injury he was “no longer Gage.” Since there is little direct evidence of the exact extent of Gage’s injuries aside from Harlow’s report, it is difficult to know exact how severely his brain was damaged. Harlow’s accounts suggest that the injury did lead to a loss of social inhibition, leading Gage to behave in ways that were seen as inappropriate. Gage’s case had a tremendous influence on early neu ology. The specific changes observed in his behavior pointed t emerging theories about the localization of brain function, or the idea that certain functions are associated with specific a eas of the brain. In those years, neurology was in its infancy. Gage’s extraordinary story served as one of the first sou ces of evidence

that the frontal lobe was involved in personality. Today, scientists better understand the role that the frontal cortex has to play in important higher-order functions such as reasoning, language, and social cognition. After the accident, Gage was unable to continue his previous job. According to Harlow, Gage spent some time traveling through New England and Europe with his tamping iron to earn money, supposedly even appearing in the Barnum American Museum in New York. He also worked briefly at a livery stabl in New Hampshire and then spent seven years as a stagecoach driver in Chile. He eventually moved to San Francisco to live with his mother as his health deteriorated. After a series of epileptic seizures, Gage died on May 21, 1860, almost 12 years after his accident. Seven years later, Gage’s body was exhumed. His brother gave his skull and the tamping rod to Dr. Harlow, who subsequently donated them to the Harvard University School of Medicine. They are still exhibited in its museum today.